Unraveling the Origins of Greek Monster Myths: Science or Imagination?

Written on

Chapter 1: The Origins of Greek Monster Myths

Have Greek monster legends been shaped more by our imaginations than by reality? Recent studies challenging the origins of the mythical Griffin have prompted a reevaluation of these legendary creatures. Let’s sift through fact and fiction.

Artwork: © Carlyn Beccia | www.CarlynBeccia.com

Chapter 1.1: The School Visit Experience

Unlike writers for adults, children's book authors face a unique challenge: school visits. If Ernest Hemingway had to charm excitable, sticky-fingered kids into reading his works, he might have consumed more absinthe and confronted more bulls.

To put it plainly: School visits are tough.

During one such visit to a local elementary school, my book, which delves into the science behind famous monsters, set the stage for educating young minds on surviving a zombie apocalypse, recognizing a kraken, or perhaps how to feed Bigfoot. (Hint: He only enjoys annoying children.)

However, I was unprepared for the lessons I would learn from them.

The students were gathered in the library, sitting cross-legged on a carpet that faintly smelled of damp Cheerios and spilled apple juice. After reading an excerpt from my book, which was mostly ignored by the restless little ones, I felt a moment of inspiration. What if I encouraged them to create their own monsters? This might just keep them busy long enough for their teachers to enjoy a moment of tranquility.

“Alright, kids,” I clapped my hands together, “I want you to draw the scariest monster you can think of! Think of terrifying figures like Frankenstein, Godzilla, or the blood-curdling Chupacabra! Give it your best shot!”

Crayons were handed out, and the children enthusiastically began their tasks. I roamed around the room, peering over their shoulders and offering encouragement.

Their initial drawings were entertaining. Mark created a lion with bat wings, while Mary depicted a crocodile with the body of a kangaroo. Little Timmy’s artwork closely resembled his father after a night of revelry, but who was I to stifle creativity?

Then, I arrived at Susie. Sweet, soft-spoken Susie, with her big, sincere eyes and tightly braided pigtails.

“What’s your monster about, Susie?” I asked, crouching to her height.

“Well…” she began with the seriousness of a young Charles Darwin, “it has the snout of a naked mole-rat because they’re really ugly, the beak of a Toucan to eat its enemies, and the legs of a Japanese spider crab since they’re super creepy.”

I gazed at her creation, a chimera so peculiar that it defied all logic. The snout was grotesque, the beak humorously out of place, and the legs unnervingly long. It was, simply put, magnificent.

The other children soon caught on, and I found myself surrounded by creations that would make Hieronymus Bosch weep with envy. One child combined an elephant’s trunk with fish fins and moose antlers, while another drew a creature with bright red bug eyes, long snake fangs, and a gigantic protruding leg. (Or at least I presumed it was a leg.)

Exiting that school visit, I couldn't help but smile. The children’s hybrid horrors revealed something significant about human creativity.

The imaginative mind constantly merges familiar fragments to create the unknown. Fear, too, is a patchwork quilt of our experiences, woven together with the fabric of imagination.

To phrase it more straightforwardly…

The creative brain thrives on borrowing. We draw from films, books, the internet, folklore, and even scientific knowledge. Picasso encapsulated it perfectly: “Good artists copy; great artists steal.” We take from diverse experiences to craft new narratives.

This school visit resonated with me when I encountered a headline disputing long-held beliefs about the origins of the mythical Griffin.

For those unfamiliar with the classics, the Griffin is a fantastical creature boasting the body and legs of a lion, alongside the head and wings of an eagle. Legend has it that the Griffin roamed the Gobi Desert, safeguarding its treasures from miners and thieves.

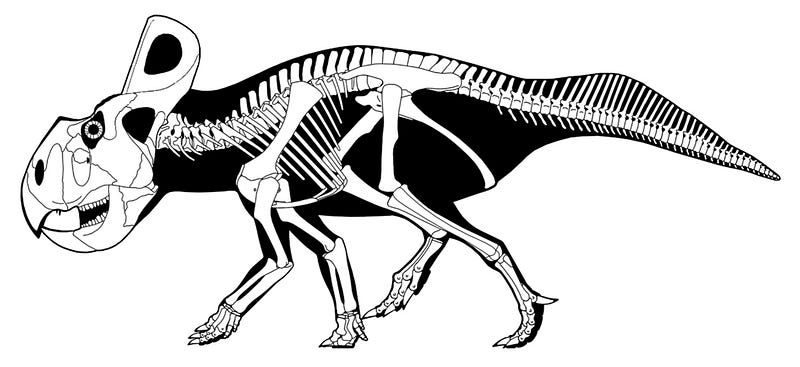

Folklorist Adrienne Mayor proposed that these myths emerged when gold seekers in Central Asia stumbled upon dinosaur bones protruding from mountains. Some of these fossils belonged to Protoceratops, whose beak and bony crest resembled the Griffin's head.

The first video titled "Gods and Robots: Myths and Ancient Dreams of Technology" delves into how ancient myths intertwine with technological aspirations, exploring the origins of legendary creatures like the Griffin.

Chapter 1.2: Geomythology and Ancient Beliefs

Understanding monster myths and cryptids through the lens of paleontology is termed “geomythology.” This field examines oral and written traditions from pre-scientific cultures to elucidate phenomena such as earthquakes, floods, and fossils. It’s akin to traveling back in time, interpreting scientific events through the perspectives of those who lacked modern scientific knowledge.

Consider fossils: they rarely represent a single animal perfectly encased in rock. Instead, floods might wash away multiple bones, trapping them together, or scavengers might scatter remains, creating a chaotic tapestry of death. When multiple animal bones fossilize side by side, it can seem as if a creature from the past had mismatched features.

In essence, if the ancient Greeks perceived fossils as real monsters, they might have misidentified the bones of different fossilized species as hybrid creatures.

For three decades, this interpretation has been the standard explanation for the Griffin legend…until now.

Recently, paleontologists Mark Witton, PhD, and Richard Hing from the University of Portsmouth revisited the fossil record. They mapped the locations of Protoceratops remains, examined classical sources linking these bones to Griffin myths, and consulted historians and archaeologists.

Their conclusion? The Griffin’s origin story doesn’t hold water.

For instance, Mayer suggested that nomadic gold seekers found Protoceratops bones in Central Asia and mistook them for the Griffin. However, these bones were discovered hundreds of miles from known gold sites.

Moreover, even if prospectors had encountered these remains, it’s unlikely they would have inspired such vivid legends. As Witton remarked in his recent study, extracting fossils from surrounding rock is no trivial task, even with modern equipment and techniques. Ancient humans lacked the scientific tools necessary to derive a rational explanation for the Griffin.

Yet, the Griffin isn't the only monster with an unusual scientific origin. Let’s explore other creatures that may have roots in real science.

Chapter 2: Scientific Explanations for Other Monsters

The second video titled "Greek Mythology for Kids | What is mythology? Learn all about Greek mythology" explains the fascinating world of Greek myths, making it accessible and engaging for younger audiences.

Medusa, one of the most notorious female monsters in Greek mythology, originally possessed great beauty until she tried to seduce Poseidon. In retaliation, Athena transformed her into a hideous being with snakes for hair.

Yet, Medusa's worst fate was not just her appearance. The legend claims that anyone who gazed upon her would turn to stone.

Similar to the Griffin, folklorists speculate that the Greeks’ narrative surrounding Medusa might have been inspired by fossilized animals. If one had no understanding of fossils, they might erroneously conclude that Medusa's stare petrified creatures. In reality, these beings were preserved in rock rather than transformed into it.

Curiously, a real phenomenon can turn creatures into stone. Lake Natron in Tanzania, known for its high alkalinity, can strip the flesh from any animal that ventures into its waters. Birds frequently found along its shores appear as if turned to stone, reminiscent of Medusa’s dreadful gaze.

The Amazons represent another fascinating aspect of Greek mythology. This legendary group of female warriors from Scythia was no mere fiction. Archaeologists have confirmed their existence. These skilled fighters wielded compact bows and arrows, battle axes, and swords, showcasing remarkable horsemanship. When the Greeks encountered these fierce women, their prowess may have inspired the myth of the centaur.

The Charybdis, a monstrous whirlpool, first appeared in Homer’s "Odyssey." Odysseus faced the daunting challenge of navigating between the six-headed sea monster Scylla and this flesh-devouring whirlpool. The Charybdis operates like a whirlpool, sometimes pulling ships beneath the waves, a reminder of nature's terrifying power.

Lastly, the Titans, a race of giants in Greek lore, likely stemmed from the discovery of large bones, like those of mastodons. As these ancient peoples unearthed massive remains, they may have imagined giant beings ruling the earth.

In conclusion, while many monsters in folklore may seem to emerge from vivid imaginations, the Greek word "mythos" signifies a "true narrative." Monster myths represent the fusion of our creativity and genuine fears.

Artwork: © Carlyn Beccia | www.CarlynBeccia.com