Survival Strategies During the Black Death: A Historical Perspective

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Black Death

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought social distancing, masks, and lockdowns to the forefront of our lives, but these measures have historical roots that stretch back to the Middle Ages. How did individuals navigate the devastating impact of the Black Death, one of the deadliest pandemics in history?

During the years 1346 to 1353, the Black Death claimed the lives of an estimated 75 to 200 million people across Eurasia and North Africa. The bacterium Yersinia pestis was responsible for this catastrophic event, transmitted to humans through fleas residing on rats. The bubonic plague, the most prevalent form, had a staggering mortality rate of around 50%, while its pneumonic and septicemic counterparts boasted a grim 100% fatality rate.

Symptoms of the disease included high fever, nausea, vomiting, and the emergence of buboes—tumor-like swellings in the groin, neck, and armpits. Historical records indicate that many succumbed to the illness within just two to seven days. Cities like Florence and Venice saw population declines of 75 to 80%, while Milan managed to lose only about 15%.

Despite the horrific toll, humanity found ways to survive. Let’s delve into the strategies employed by ordinary citizens, healthcare providers, and authorities during this tumultuous time.

In the video "How did Medieval People respond to the Black Death?" we explore the various responses and survival tactics employed by individuals during this pandemic.

Section 1.1: Early Responses to the Plague

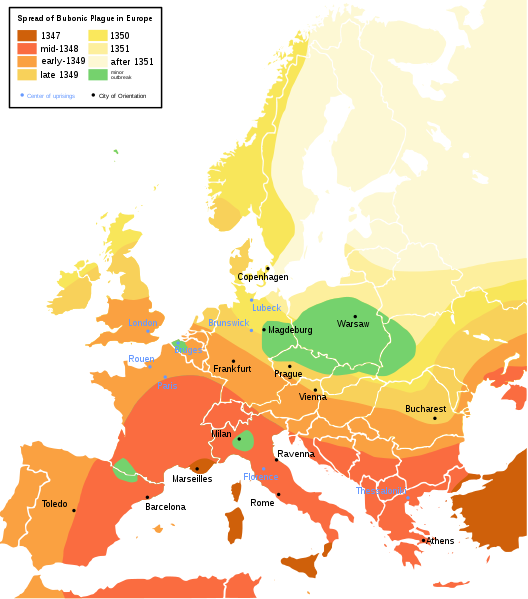

The initial emergence of the Black Death in Europe occurred in 1347, with cases reported in Asia Minor, Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. By 1348, the plague had reached Paris, and by 1349, London and Frankfurt were not spared. As cities faced severe population losses, many, like Milan, implemented drastic measures to curb the spread of the disease.

In Milan, officials took the extreme step of sealing the homes of infected individuals. Rather than merely restricting movement, they literally bricked up doors and windows, leaving those inside to perish. While this may appear harsh by modern standards, it proved effective; Milan experienced significantly lower mortality rates compared to cities like Florence.

Many regions in Eurasia, including Poland, instituted border closures to prevent the movement of the disease. The journey from Prague to Krakow took eight days by horseback, allowing time for symptoms to manifest. This isolation helped prevent further spread within national borders.

Section 1.2: Quarantine as a Survival Strategy

Quarantine measures were pivotal during the Black Death and remain relevant today. The port city of Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik, Croatia) was the first to mandate isolation for those arriving from afflicted areas. Travelers were required to spend time on a remote islet for disinfection, demonstrating an understanding of the disease's incubation period.

The term "quarantine" itself originates from the Italian word "quarantino," which referred to a 40-day isolation period. Ragusa was also a pioneer in establishing dedicated plague hospitals, known as lazarettos, that provided care for victims.

Chapter 2: Migration and Social Changes

The Black Death predominantly afflicted urban centers, prompting many urban elites to flee to rural areas. Interestingly, urban laborers, who had migrated from the countryside, also departed in droves, unwilling to work for lower wages. This mass exodus contributed to the emergence of a burgeoning middle class that could afford luxuries previously unattainable.

In the video "The Black Death - The Great Bubonic Plague of the Middle Ages," we further investigate the societal changes brought about by the pandemic and the responses of various communities.

Section 2.1: The Role of Plague Doctors

Since the early outbreaks of the Bubonic Plague, cities employed plague doctors to care for infected individuals. Their demand surged during the Black Death. Clad in long overcoats and beaked masks filled with fragrant oils, these doctors believed they could ward off "bad air," a misconception rooted in the Miasma theory.

Although often not formally trained, plague doctors were tasked with counting victims and enforcing quarantines. While some legitimate medical professionals existed, many relied on dubious methods such as bloodletting.

Section 2.2: Cultural Responses to the Plague

During the Black Death, the notion that foul air transmitted disease led people to cover their noses with handkerchiefs or smell flowers. Fragrances became increasingly popular, believed to combat the pestilence.

Religious fervor also intensified, with some individuals engaging in self-flagellation as a form of penance, mistakenly thinking it would absolve their sins. Unfortunately, this practice often led to further spread of the disease, as they congregated in densely populated areas.

The limited medical knowledge of the time allowed charlatans to exploit the fears of the populace. Despite the grim realities, public officials endeavored to implement measures to control the epidemic, albeit sometimes with severe consequences.

The Black Death stands as one of humanity's darkest epochs. Yet, many strategies we employ today to combat pandemics have their roots in this historical crisis. For those interested in the impact of diseases on civilizations, the Antonine Plague's role in the Roman Empire's decline is a compelling topic to explore.