The Dietary Link to Cancer: Unpacking the Evidence

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Cancer Mechanisms

Cancer encompasses various diseases that share specific characteristics, including resistance to cell death, ongoing cell growth signals, and altered energy metabolism. One critical aspect to consider is the acquired resistance to apoptosis. In healthy conditions, cells that do not pass specific checkpoints during cell division are directed to undergo programmed cell death, or apoptosis, essentially a form of self-destruction. This process allows cells to shrink gradually, preserving surrounding tissues—a phenomenon that acts as a natural defense against cancer development. Conversely, inhibiting apoptosis can accelerate tumor growth.

Unlike apoptosis, necrosis leads to the cell's rupture, releasing inflammatory cytokines into the surrounding area, resembling an explosive event. This necrotic cell death can attract immune cells that promote tumor growth through angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, thus facilitating the survival of cancer cells.

The tumor microenvironment consists of surrounding non-cancerous cells and molecules that can be manipulated by cancer to support its growth. If apoptosis dominates over necrosis in a microenvironment, it may prevent cancer development. This raises the question: How does an individual's broader environment impact cellular microenvironments? Can dietary choices maintain optimal apoptosis levels? Are cruciferous vegetables effective in reducing cancer risk?

Cruciferous vegetables are rich in compounds like sulforaphane, known to induce apoptosis in various cancer types, including breast, colon, and prostate cancers. Notably, sulforaphane found in broccoli sprouts, bok choy, and cabbage has shown potential in combating acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most prevalent blood cancer in children.

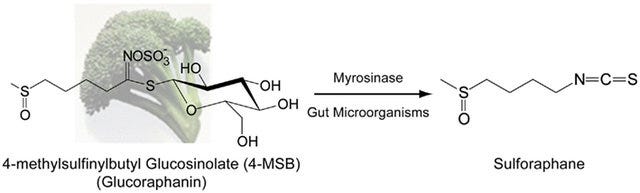

A study conducted in 2008 revealed that consuming raw broccoli led to quicker absorption and higher levels of sulforaphane in the bloodstream compared to cooked broccoli. Cooking methods such as boiling or microwaving at high temperatures can deactivate myrosinase, an enzyme necessary for converting glucosinolates like glucoraphanin into isothiocyanates (ITCs) such as sulforaphane.

If raw vegetables are unappealing, incorporating powdered brown mustard seeds, which are rich in myrosinase, into cooked broccoli can enhance sulforaphane absorption. While cooking can denature the plant's myrosinase, human gut microbiota also contain myrosinase enzymes that can assist in the conversion of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane, though to a lesser extent.

Chapter 2: The Role of Resistant Starch

The first video titled "The Link Between Nutrition and Cancer" discusses how dietary choices impact cancer risk. It explores the importance of various food groups in potentially lowering the risk of cancer.

Can resistant starch consumption help prevent colorectal cancer? This type of cancer ranks as the third most common in the Western world and is notably on the rise among younger adults. Observations from 1973 indicated that immigrants adopting a Western diet experienced increased colon cancer rates.

Native South Africans, who consume a diet rich in fermented whole grain-maize porridge, exhibit some of the lowest colorectal cancer rates. This diet is high in resistant starch, which specific gut bacteria can ferment to produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that encourages apoptosis and has numerous anti-inflammatory benefits.

Butyrate serves as a primary energy source for colon cells, lowers intestinal pH, and hinders the development of tumorigenic cells. Research shows that colorectal cancer patients often have significantly fewer butyrate-producing bacteria compared to healthy individuals. Butyrate inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), promoting the expression of genes that facilitate cell death and apoptosis.

Food exchange studies have demonstrated that when African Americans switch to a diet rich in resistant starch, their gut microbiota quickly adjust, increasing butyrogenesis and reducing colonic inflammation. The Native African diet included high-fiber foods like lentils, okra, and mango, while the Western diet often comprised high-fat and processed items.

Not all fibers are equal, particularly resistant starch, which is defined as starch that escapes digestion in the small intestine and reaches the colon intact. There are five types of resistant starch, and the first three are commonly found in human diets:

- RS1: Starch trapped within plant cell walls, found in whole grains and legumes.

- RS2: Native, granular starch, such as in raw potatoes and green bananas.

- RS3: Retrograded starch from cooked and cooled starchy foods.

The recommended daily intake for resistant starch has not been firmly established, complicating assessments of its effects on cancer risk. Nevertheless, approximately 20 grams per day may be required for digestive health benefits.

The absence of adequate RS3 could explain why colorectal cancer tends to occur more frequently in the distal colon than in the proximal colon. Most dietary fibers ferment predominantly in the proximal colon. For optimal butyrate production, RS3 appears particularly crucial, especially when combined with RS2.

Research indicates that RS3 can significantly enhance butyrate production while increasing beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacteria in the colon. Common sources of RS3 include cooked and cooled rice, potatoes, green plantains, and cassava. A study found that a high-resistant starch diet significantly decreased fecal pH, which is associated with a reduced risk of bowel cancer.

Chapter 3: Assessing Red Meat Consumption

The second video, "Nutrition and Cancer: Does It Make a Difference?" delves into the role of dietary choices, including red meat consumption, in cancer risk.

Research has consistently linked red meat intake to colorectal cancer, yet a meta-analysis of 35 studies found these associations to be weak and not statistically significant. Interestingly, red meat's impact appears more pronounced in cancers of the distal colon rather than the proximal colon.

Observational studies often encounter "healthy user bias," suggesting that individuals who follow one healthy behavior are likely to engage in others, complicating the analysis of red meat's isolated effects. Additionally, the geographical context influences outcomes, with stronger associations seen in American populations compared to European and Asian groups.

Even if a connection between red meat and colon cancer were firmly established, incorporating resistant starch might mitigate any adverse effects. High-amylose maize starch can shift colonic fermentation from protein to carbohydrate sources, potentially enhancing the production of short-chain fatty acids.

Chapter 4: The Organic Debate

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer identified certain organophosphate pesticides as probable human carcinogens, raising questions about the impact of organic food consumption on cancer risk. A 2018 study revealed that individuals primarily consuming organic foods had a significantly lower likelihood of developing certain cancers compared to those who rarely consumed organic options.

However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously due to potential confounding health behavior biases. Individuals opting for organic foods may differ in health attitudes and behaviors compared to those who do not, which could skew results.

Dr. Jorge E. Chavarro of Harvard noted that the assumption of lower pesticide exposure from organic food consumption lacks empirical backing. Nevertheless, prior research supports a correlation between self-reported dietary intake and urinary pesticide levels.

Future research is warranted to delve deeper into the relationship between organic food intake and cancer risk.