# The Resurgence of Physiognomy: Art or Pseudoscience in Modern Times?

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Physiognomy's Renaissance

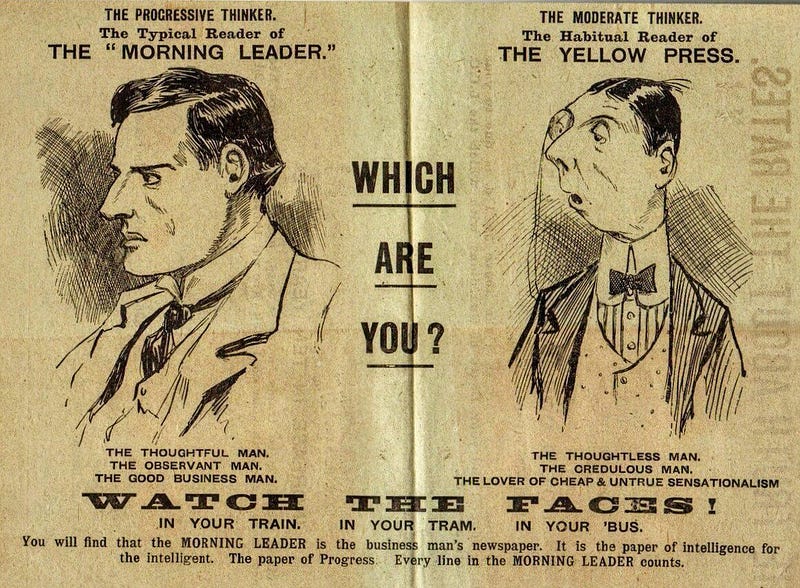

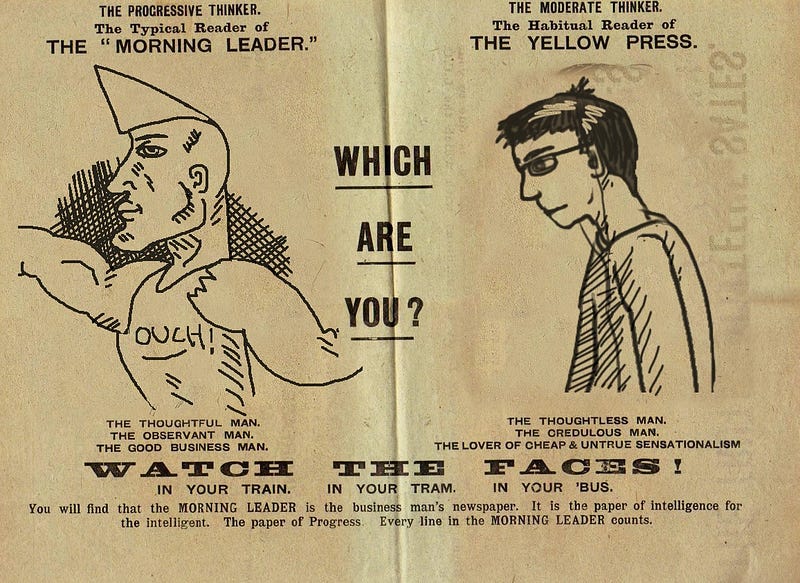

Physiognomy, the practice of deducing character from physical appearance, is witnessing a revival in contemporary discourse. The phrase "physiognomy remains undefeated" circulates on platforms like Twitter, often with a hint of irony. While many dismiss it as a pseudoscience, its resurgence aligns with broader ‘post-truth’ trends that favor intuition over empirical evidence.

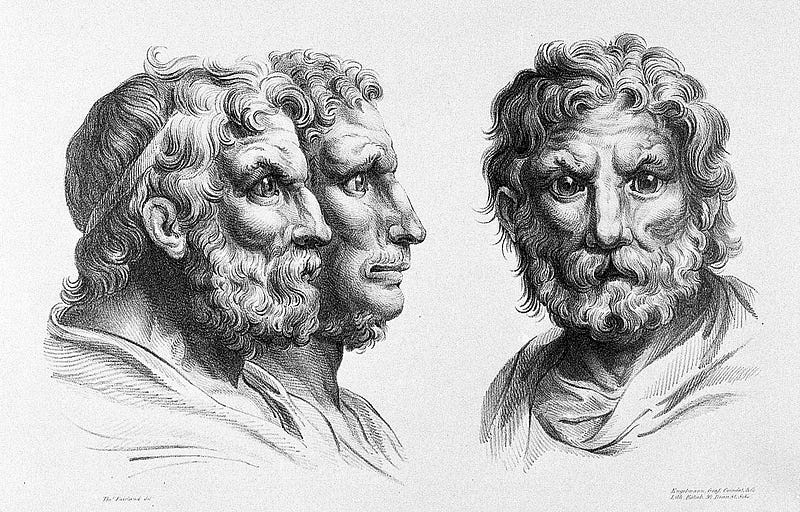

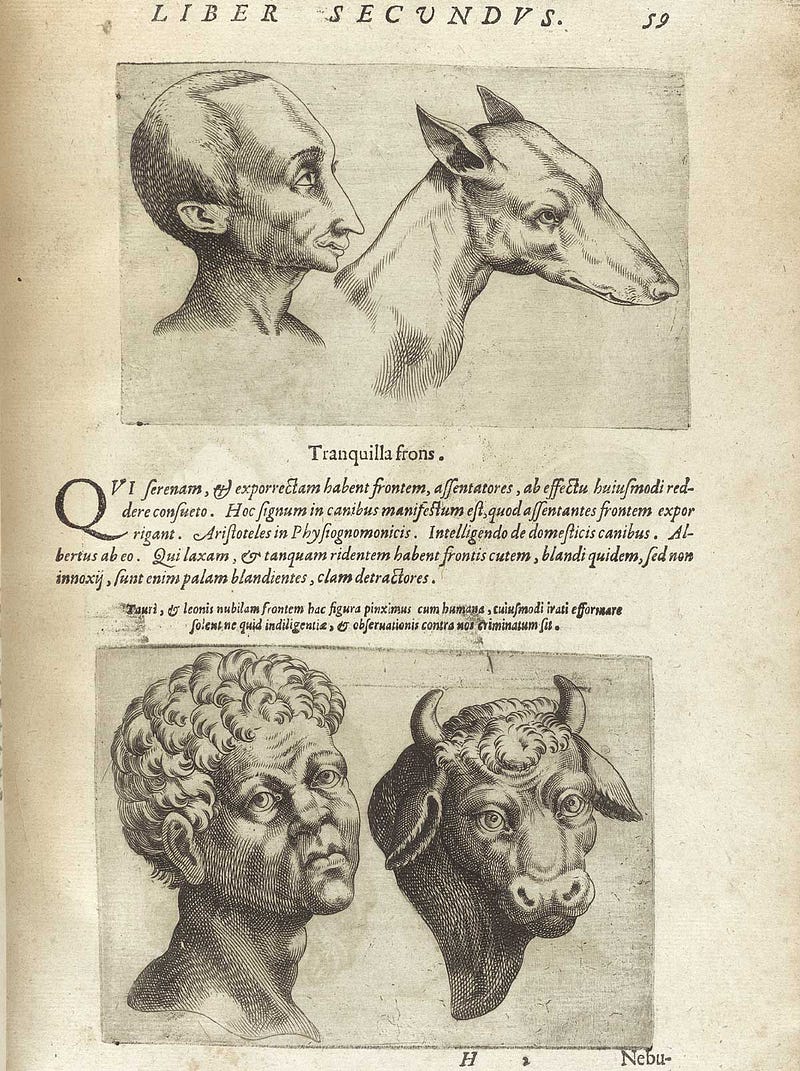

Tracing back to ancient times, physiognomy emerged as a medical discipline rooted in interpreting visible signs and symptoms (Baumbach). The earliest surviving text on the subject, the Physiognomonica, is incorrectly attributed to Aristotle. In her work, “The Beginnings of Physiognomy in Ancient Greece,” Maria Michela Sassi notes that this text, dating back to 300 BCE, discusses physical traits as indicators of one’s inner character. The ancient belief was that the human body functioned as a canvas, inscribed with divine messages about an individual’s fate (Salin).

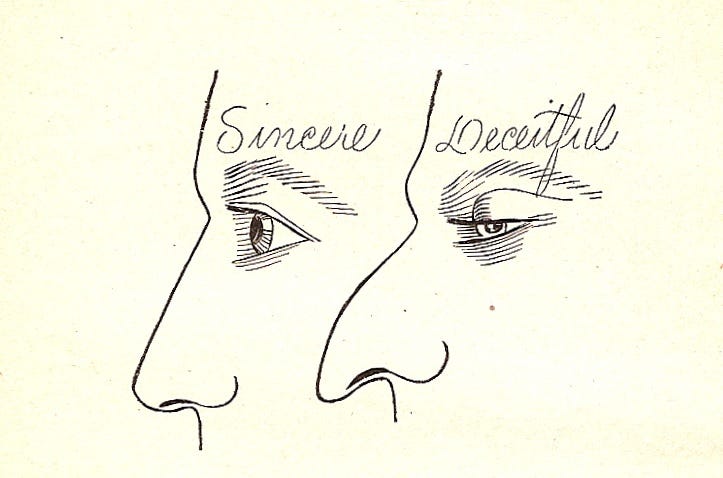

According to this view of interpretability, physiognomy is often referred to as face-reading. Sibylle Baumbach, in her book Shakespeare and the Art of Physiognomy, describes it as primarily an interpretive practice. Shakespeare notably employs this motif in his character sketches, suggesting that the face serves as a narrative of one’s character. For example, he posits that one can read fortunes and misfortunes from the face, likening the forehead to a cover page that reveals the essence of a character (Baumbach).

Interest in physiognomy dwindled during the Early Middle Ages but re-emerged in Christian Europe during the High Middle Ages as part of a broader revival of scientific and philosophical knowledge influenced by Greek, Roman, and Arabic traditions. Steven J. Williams notes that by the thirteenth century, what Jole Agrimi termed a "renaissance" of physiognomic thought began to take shape.

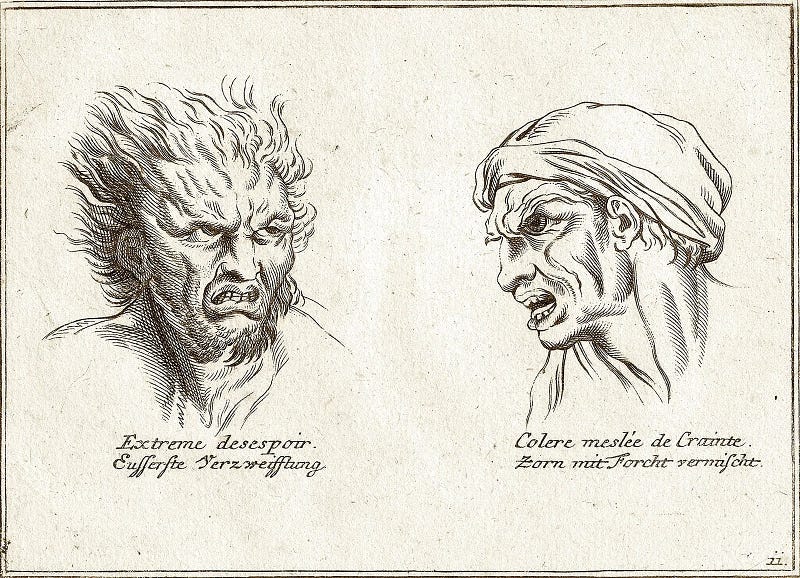

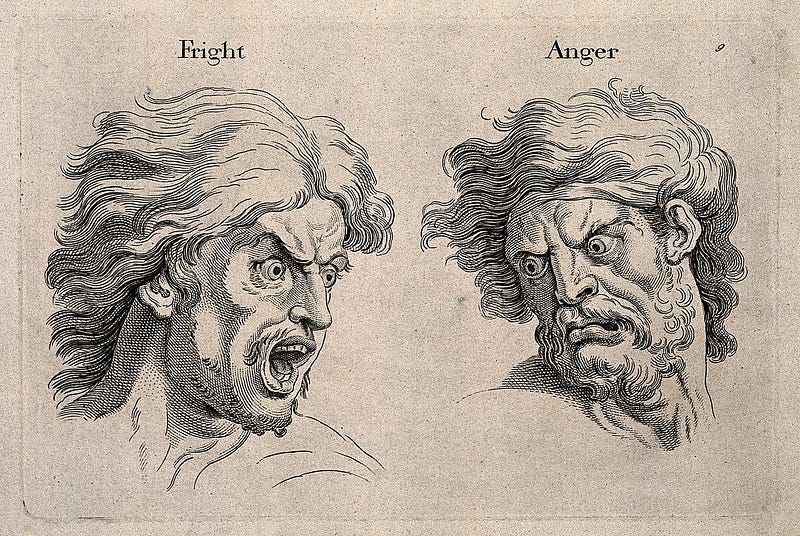

In the eighteenth century, Swiss theologian Johann Kaspar Lavater released Essays on Physiognomy, which, while mistakenly credited with founding physiognomic theory, made significant distinctions between inherent and transient facial features. Lavater introduced the notion that the physiognomy, or the static structure of the face, contrasts with pathognomy, the fleeting expressions shaped by emotions. He asserted that the face serves as a narrative, containing its own interpretation: “Gesicht aber bleibt immer Text, in dem der Kommentar schon mitbegriffen ist” [The face remains always a text, which already contains its commentary] (Sibylle).

Baumbach emphasizes that while these categories are distinct, they are interconnected; habitual expressions can etch themselves into one’s physiognomy. For example, someone who frequently frowns may develop a permanently furrowed brow, signaling a serious disposition.

This distinction arose partly from debates with scientist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, who criticized the rigid reliance on physical traits to ascertain character. Lichtenberg contended that the true indicators of moral character lie in the marks left by life experiences rather than innate features. He provocatively suggested that if physiognomy were valid, children showing signs of future criminality should be executed preemptively based on their appearances (Baumbach).

Modern critiques echo Lichtenberg's concerns, branding physiognomy as an "unlawful, highly speculative, and utterly inflexible science." Such critiques have roots in antiquity, as illustrated by Socrates’ encounter with the physiognomist Zopyrus. After assessing Socrates, Zopyrus claimed to detect signs of a "weak and depraved nature." However, the audience, familiar with Socrates’ true character, found amusement in Zopyrus’ judgment. Socrates himself acknowledged these perceived flaws, attributing them to nature but asserting he had overcome them through reason (Baumbach).

Socrates’ perspective reflects an early assertion that "DNA is not destiny." The critical flaw of physiognomy lies in its failure to recognize how societal perceptions—often prejudiced—shape individual identities from birth. When Socrates speaks of overcoming his nature, he may also reference the bias of his contemporaries, who engaged in physiognomic stereotyping. The struggle against others' expectations is what he triumphed over. Even Nietzsche, following the physiognomic theorist Cesare Lombroso, critiques Socrates’ looks, labeling him as both ugly and indicative of a flawed spirit. Nietzsche remarks that in Greek culture, ugliness often serves as a disqualification of one’s character: “monstrum in fronte, monstrum in animo” (a monster in appearance is a monster in spirit).

Physiognomy may lack scientific credibility, but its implications can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, shaping perceptions and lives in profound ways.

Chapter 2: The Contemporary Implications of Physiognomy

The discussion surrounding physiognomy, its historical context, and its modern-day relevance unveils much about human psychology and societal biases. Understanding these dynamics is crucial in navigating today's complex social landscape.