The Multiverse Challenge: Evil and the Nature of God

Written on

Chapter 1: The Multiverse and Its Implications

The concept of the multiverse raises significant questions regarding the existence of an all-good, all-powerful deity, particularly in the context of the fine-tuning argument. If infinite universes exist, the reasoning follows, then we don't necessarily require a fine-tuner to clarify why our universe is conducive to life. However, certain multiverse models present a more direct challenge. The many-worlds interpretation proposed by Hugh Everett III and Max Tegmark's modal realism suggest the existence of worlds that an inherently good deity would not permit. While these theories differ fundamentally, they both foresee realms filled with suffering and despair.

Many thinkers argue that the suffering present on Earth alone questions the existence of a benevolent God. Yet, others counter this by suggesting potential justifications for God's allowance of a world like ours. Notably, virtues such as forgiveness, bravery, and resilience can only emerge in the face of hardship and adversity. The most remarkable moral accomplishments of humanity seem to necessitate such challenges.

Nevertheless, numerous atrocities occur without any apparent purpose. The implications of Everett's and Tegmark's theories suggest the existence of countless horrifying universes populated solely by individuals in distress. For those who hold a traditional view of God as a loving creator, these conclusions are understandably troubling, raising questions about the validity of these theories.

"This perspective invites contemplation on the nature of suffering and divine purpose."

Section 1.1: The Many-Worlds Interpretation Explained

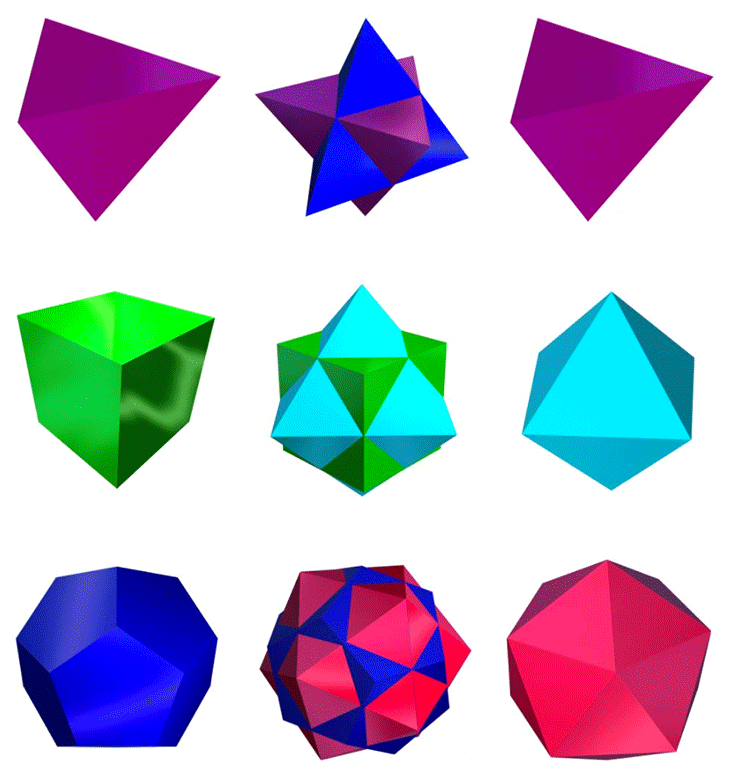

Everett's many-worlds interpretation originates from quantum mechanics' complexities. The Schrödinger equation, a fundamental principle of quantum theory, describes the changing states of particles. However, it predicts "superpositions" of states that seem incompatible, such as a coin landing both heads and tails. This raises the question: why do we never witness these combined states? A common explanation among theorists is the phenomenon known as "wave function collapse," leading to a definitive outcome.

In the 1950s, Everett introduced a revolutionary approach. His theory does not involve collapses; instead, it posits that all superposed states exist as parts of relatively isolated, equally real worlds. Some universes feature a coin landing heads, while others show it landing tails. This branching structure leads to multiple overlapping realities stemming from an initial state.

Everett's many-worlds and Tegmark's modal realism imply the existence of innumerable horrific universes. Traditional quantum theory suggests a minuscule chance for catastrophic events. However, the many-worlds interpretation asserts that these possibilities are actual occurrences, predicting branching universes where disastrous outcomes unfold.

Section 1.2: The Role of God in the Multiverse

A religious person might hope that God would intervene to eliminate the branches of suffering, yet philosopher Jason Turner argues that such intervention would contradict the Schrödinger equation. If God prevents the emergence of the most dreadful universes, then deterministic laws would not accurately describe multiverse evolution. Only those states deemed "good enough" by God would manifest.

However, even if this argument fails, there remains a case for believing in God amidst the many-worlds interpretation. This multiverse is merely an expansive physical realm, and discovering ourselves within it resembles finding a universe with an abundance of inhabited planets—some mirroring our planet's darkest aspects and others reflecting its brightest. The existence of an afterlife could provide meaning to suffering, suggesting that even in the bleakest Everettian worlds, individuals might experience an afterlife.

Chapter 2: The Mathematical Multiverse

Exploring how the concept of evil prevails when good individuals remain passive in the face of adversity.

Examining whether the presence of evil absolves God from being the universe's originator.

Tegmark's multiverse, unlike Everett's, emerges from modal realism, positing that every conceivable scenario is as real as our universe. While philosophers often view possible worlds as abstract entities existing outside space and time, Tegmark contends that these possibilities are intrinsically linked to mathematical structures.

His theory necessitates the existence of universes characterized by short and miserable lives devoid of afterlife. If our universe is fundamentally a mathematical construct, every conceivable arrangement of matter corresponds to a universe, including those filled with pointless suffering—similar to the most tragic branches of Everett's world-tree and infinitely more.

In essence, Tegmark's theory implies a realm of existence where short, miserable lives and absence of an afterlife are inevitable. This leads to a disheartening picture: a God who loves all beings yet must watch infinite lives unfold in despair would be embroiled in tragedy.

Despite the unsettling implications of the multiverse theories, belief in God need not falter. The possibility of a multiverse may suggest that God has reasons for creating multiple realities, each with its own unique qualities. A divine being could be expected to craft worlds of varied experiences—some filled with vibrancy and others resembling sparse minimalist art, potentially including intelligent beings.

The insights of physicists like Alan Guth and Andrei Linde, proposing a multiverse of eternally inflating fields, or Paul Steinhardt and Neil Turok's cyclical universe concept, might align with this theological perspective. Ultimately, our world could be one of many, deemed good enough for divine creation, and the notion of a multiverse may enhance the belief that our universe is part of a greater, benevolent design.

Dean Zimmerman, a philosophy professor at Rutgers University, explores these profound questions further. Follow him on Twitter @deanwallyz.