# Harry Styles and the Implications of AI Deepfakes

Written on

Chapter 1: The Emergence of the "Liar's Dividend"

In 2019, legal experts Danielle Citron and Robert Chesney introduced a significant concept known as the "liar's dividend." Their concerns centered on how AI-generated deepfakes could potentially disrupt the political landscape. As technologies for creating convincing fake videos and audio became more accessible, individuals seeking to manipulate elections could easily fabricate media targeting politicians.

Fortunately, we have yet to witness a major political season in North America affected by this phenomenon. Fast forward four years, and producing high-quality fake media is easier than ever. However, the predominant applications of deepfakes are not in politics but rather in adult content—specifically, efforts to degrade female celebrities—and scams, such as impersonating a relative's voice for fraudulent purposes.

Why haven’t we seen a surge of political deepfakes? One reason may be that crafting a truly convincing political fake requires considerable effort. Additionally, as scholar Hany Farid pointed out, “shallow fakes” often suffice. For instance, if one aims to diminish Joe Biden's credibility, there's no need for a sophisticated fake video; merely using an unflattering image with misleading captions can be enough to sway public opinion.

But the most intriguing aspect of Citron and Chesney’s analysis lies in their foresight regarding a secondary issue: widespread deepfakes could foster a culture of cynicism among the public, leading to skepticism about the authenticity of all media. This environment would provide an easy escape for wrongdoers; if incriminating footage were released, they could simply claim it was fabricated.

This phenomenon is what they termed the "liar's dividend." As they articulated, “As awareness of deepfakes increases, public figures caught in genuine acts of misconduct will find it easier to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the evidence against them.” For instance, if deepfakes had been prevalent during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Donald Trump could have more easily dismissed the infamous audio recording in which he boasted about groping women. As society becomes more attuned to the risks of deepfakes, trust in news media may erode.

I believe the liar’s dividend presents a more immediate threat in our deepfake era. We are likely to spend considerable time debating the authenticity of various media.

A compelling illustration of this can be found in a recent article from 404 Media regarding deepfakes within the Harry Styles fan community. As reported by Jason Koebler, the fandom is currently embroiled in disputes over whether certain music tracks circulating online are authentic Harry Styles and One Direction material or AI-generated fakes.

You should definitely check out the full article; it’s quite enlightening! In summary, within the Harry Styles community, fans frequently post on Discord claiming to have access to leaked or unreleased tracks, requesting substantial payments—often around $400—before sharing them publicly.

Recently, a pseudonymous Discord user managed to raise enough funds to release some questionable tracks. However, when fans scrutinized these recordings, a fierce debate erupted: some believed they were deepfakes, while others contended they were genuine.

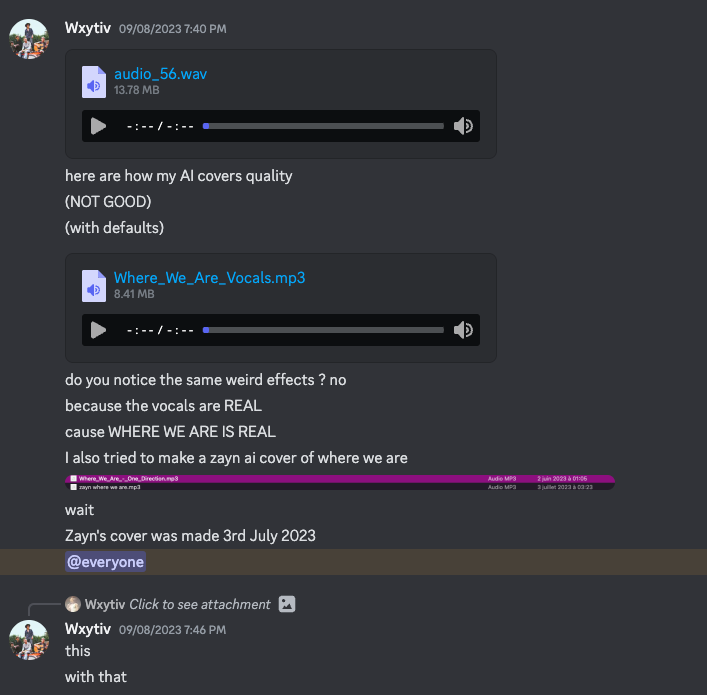

To support their positions, fans would juxtapose snippets of known AI-generated music with the disputed tracks, engaging in detailed comparisons regarding sound quality and authenticity. The individuals selling these tracks also shared snippets of both potentially legitimate leaks and AI-generated songs, creating a confusing mix that blurred the lines between real and fake. One seller, Wxytiv, even posted, “Here’s how my AI covers sound (NOT GOOD),” alongside what they claimed was a legitimate leak for contrast. “Do you notice the same odd effects? No, because the vocals are REAL.”

This scenario exemplifies the established "scamming" issue associated with deepfakes, as Koebler highlights. The rise of AI-generated music has complicated the landscape of music leaks, making it increasingly likely for fans seeking authentic tracks to fall victim to scams. In a recent incident, a scammer who sold AI-generated Frank Ocean "leaks" on Discord made thousands before disappearing. The advanced capabilities of AI generation, combined with the fervor of superfans eager for new content, create a perfect storm for deception.

This situation isn't a direct representation of the liar's dividend as articulated by Citron and Chesney, but it is closely related. At the heart of this Harry Styles controversy is the growing uncertainty surrounding the authenticity of any given media due to the mere existence of deepfakes.

It is entirely plausible that we will soon experience serious implications of deepfakes in political contexts. The upcoming U.S. presidential election stands as a potential battleground for such occurrences. While we have been fortunate thus far, that luck may not last.

However, as the example of Harry Styles illustrates, the effects of deepfakes reach beyond politics. Issues of media authenticity are present across various domains, including pop culture, the legal system, journalism, healthcare, and advertising.

Therefore, I predict that the liar’s dividend will not only taint political discourse but will also emerge swiftly across other sectors of human activity.

Interestingly, there may be a silver lining. Observing the Harry Styles debate reveals that many fans are cultivating a keen interest in analyzing media for signs of artificial production. These fans are becoming increasingly sophisticated in their evaluations. Techniques like the "Mel Spectrogram," currently niche, may gradually gain mainstream traction. If fortunate, we might witness a public that possesses a nuanced understanding of media authenticity, avoiding a total descent into epistemological nihilism.

We've observed similar trends with past media forms. In a previous piece for Smithsonian magazine, I discussed how early photo manipulation techniques were rudimentary—essentially cutting out images and pasting them together to create false impressions. While these methods initially succeeded in deceiving people, as more individuals gained access to personal cameras and experimented with photo editing, public awareness of manipulation techniques increased, making them less susceptible to deception.

Will we reach a similar level of public literacy regarding AI deepfakes? The answer remains uncertain. This issue is multifaceted and intertwined with the broader decline of trust in institutions in America, making predictions challenging.

Nevertheless, the liar’s dividend? That is imminent, and we will see its impact soon.

(Enjoyed this content? Hit that “clap” button and show your appreciation! You can click it up to 50 times per reader!)

I’m a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and Wired, and author of “Coders.” Follow me on Mastodon or Instagram.