How Early Astronomers Navigated Office Politics for Job Security

Written on

Chapter 1: The Dreamy Stereotype of Early Astronomers

When picturing early astronomers, one often imagines them as the quintessential daydreamers, engrossed in the cosmos while others around them focus on terrestrial matters. Think of a friend who often drifts into deep thought, seemingly lost in their own world.

Einstein exemplified this archetype, visualizing concepts in his mind and often finding himself in trouble at school for appearing inattentive. Dr. Craig Wright, in The Hidden Habits of Genius, recounts how Einstein would envision himself suspended on rays of light, even while walking to work and pondering what it would look like if a car sped away from a city clock at light speed. Those around him likely had their own concerns and would prefer not to be trampled by a wandering physicist.

While Galileo may have shared this imaginative quality, he also possessed a practical side. He could impart valuable lessons about navigating the complexities of workplace relationships. Many astronomers of his era were adept in these arts, and while we celebrate their astronomical contributions, they also had keen insights into improving their standing on Earth.

This journey begins with understanding how to cultivate a positive relationship with superiors. The art of strategic flattery can open doors. As Robert Greene articulates, “Never outshine the master.”

Section 1.1: Galileo's Quest for Financial Stability

In the 1600s, Galileo faced a pressing dilemma that had nothing to do with celestial bodies—it was financial insecurity. Lacking funds, he frequently sought patrons to support his studies. He often found himself creating inventions or dedicating works to various nobles, which resulted in gifts but also reinforced a cycle of dependency.

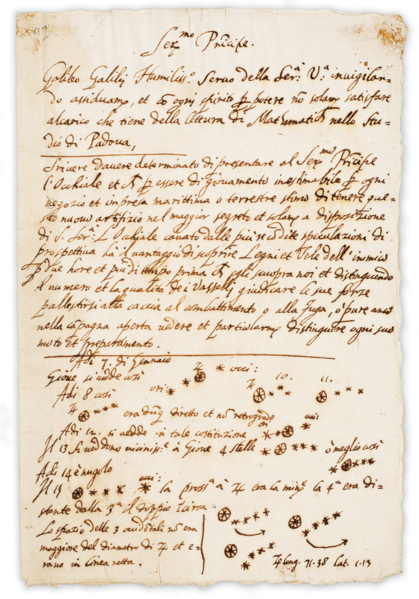

Greene notes that this arrangement led to a life filled with uncertainty. To break free from this cycle, Galileo sought a more sustainable solution, which came in 1610 with his discovery of Jupiter's moons.

Instead of dividing his discovery among multiple patrons, Galileo decided to focus solely on the affluent Medici family, whose emblem represented the god Jupiter. By framing the discovery as a significant event for the Medici, he cleverly tied their legacy to his findings. He even aligned the date of his announcement with the coronation of Cosimo de’ Medici, presenting the moons as reflections of the four Medici brothers.

This strategic flattery paid off; Cosimo II appointed Galileo as the court philosopher and mathematician, providing him with a steady income. Greene emphasizes that this singular act led to more progress than years of seeking support.

Chapter 2: Making Connections with the Cosmos

Section 2.1: The Case of Uranus

Our next case study in celestial connection involves Uranus—not as scandalous as it sounds, though the name does invite some humor. In the late 1700s, musician-turned-astronomer William Herschel was drawn to the stars, creating his own telescopes with polished metal mirrors. The limitations of local foundries prompted him to forge larger mirrors himself, a risky endeavor.

Professor Jim Al-Khalili narrates Herschel's journey in his documentary, revealing the remnants of molten metal spills in his home. After crafting a new telescope, Herschel discovered a new planet, a monumental find that could bolster his standing.

He initially named the planet “Georgium Sidus” in honor of King George III, who, grateful for the tribute, granted Herschel a pension, allowing him to dedicate himself solely to his research. This eventually led to Herschel creating one of the first diagrams of the Milky Way. The planet would later be renamed Uranus to align with the nomenclature of other celestial bodies.

Section 2.2: Sir Charles Scarburgh's Royal Connection

Sir Charles Scarburgh lived through tumultuous times during the English Civil War. After the execution of Charles I, he aligned with the royalists, which required him to transfer schools while studying medicine. Despite this upheaval, he earned acclaim and became a founding member of the Royal Society.

Upon the restoration of the monarchy, Scarburgh was appointed as the personal physician to Charles II, and he honored the king by naming a star after him. He chose Alpha Canum Venaticorum, referring to it as Cor Caroli, or "The Heart of Charles," a nickname that endures today.

Michael Molinsky of the University of Maine at Farmington notes that Scarburgh was eventually knighted for his service to the crown and continued to serve the royal family even after Charles II's passing.

Section 2.3: A Celestial Guide to Thriving at Work

“Galileo did not challenge the intellectual authority of the Medicis with his discovery, nor did he make them feel inferior. By aligning them with the stars, he allowed them to shine among Italy's courts. He never outshone the master but instead helped the master shine brighter.” — Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power.

Greene explains that those in power often grapple with insecurities, particularly when surrounded by talented subordinates. To avoid conflict, it’s crucial not to appear as a threat to their status. Instead, direct your successes towards enhancing their reputation.

Many early astronomers knew how to navigate this delicate balance. Galileo made his discoveries relevant to the Medicis, solving his financial troubles in the process. Herschel's work caught King George III’s attention, securing him a stable income. Similarly, Scarburgh's connection to a star solidified his place in royal favor.

By ensuring your superior feels valued while showcasing your own talents, you become indispensable. The Medici family couldn’t afford to lose Galileo due to the prestige he brought them, much like how Herschel's brilliance would attract another monarch’s interest. Scarburgh's loyalty earned him positions in three royal courts.

While the image of astronomers as mere dreamers persists, these early figures were astute navigators of both the stars and earthly relationships. Galileo, Herschel, and Scarburgh exemplified how to shine without overshadowing their superiors.

Although you may not be able to name a star after your boss, you can take a page from their book by helping your superior shine brighter through your own accomplishments.