Baby Fat: More Than Just a Cute Appearance

Written on

Understanding Baby Fat

The notion of "baby fat" often brings smiles and nostalgia, but it serves a significant evolutionary purpose. At birth, human infants possess the highest percentage of body fat among all species.

As a child, I frequently heard, “Oh, you still have your baby fat!” Despite my healthy weight, I seemed to retain those round cheeks and chubby belly longer than my peers. “Don’t worry, dear,” my mom would say, “it helps keep you warm. Just a bit of insulation.” While she was partially correct, the reality is far more complex.

Years later, I found my path as an anthropologist focusing on nutrition and human growth. It turns out I wasn't alone in my pudginess; humans are the fattest species at birth, boasting about 15% body fat—more than any other species. While some mammals, like guinea pigs and harp seals, have notable fat percentages at birth (11% and 10%, respectively), none match our newborn fat levels.

Most fat in animal infants, such as seal pups and piglets, accumulates postnatally. In contrast, human infants continue to gain fat, peaking between 4 and 9 months with a body fat percentage of approximately 25%. Following this peak, fat levels gradually decline. This phase leads to a period in childhood when many humans reach their lowest body fat percentage, unless, of course, they face genetic challenges.

Why is it that human babies are born with such excess fat? While many suggest that this layer serves as insulation against cold, evidence doesn’t strongly support this view. Populations in colder climates don’t show significantly higher body fat, and increasing fat layers don’t necessarily aid in temperature regulation.

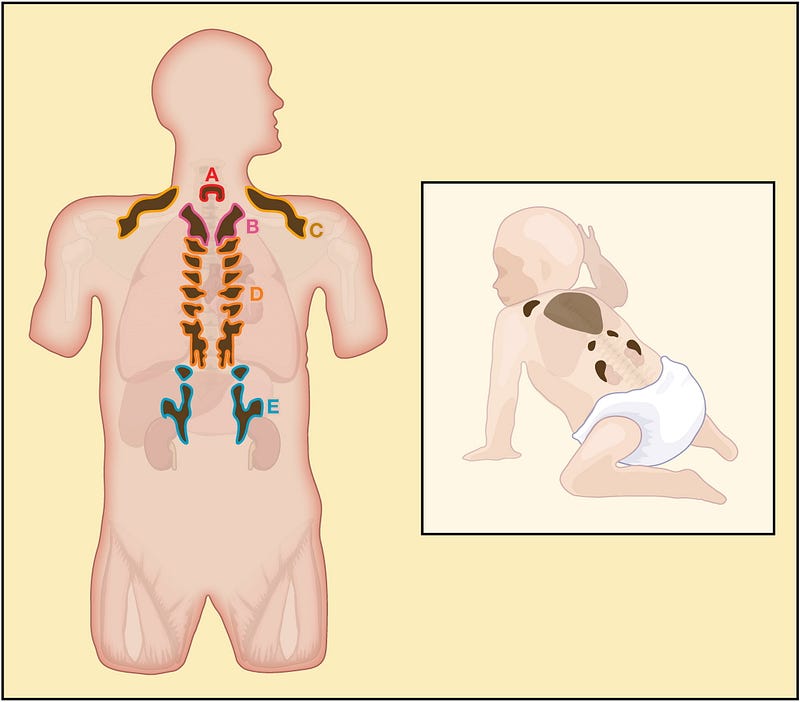

Humans have two types of fat: white fat, which is the common type, and brown fat, or brown adipose tissue (BAT). BAT is crucial for all neonatal mammals, particularly humans, as we cannot rely on shivering to warm ourselves. BAT functions as an internal heat generator, burning white fat to produce warmth. However, by adulthood, BAT comprises only about 5% of an infant's total fat.

So if baby fat isn't primarily for warmth, what purpose does it serve? Fat acts as an energy reserve, critical for humans and other mammals, especially during times of food scarcity. Given our brains' high energy demands—using about 50-60% of an infant's energy budget—adequate fat reserves are essential. These stores are particularly vital during the post-birth fasting period, as the first milk (colostrum) is rich in protein and nutrients but lower in sugar and fat.

In addition to supporting their energy-intensive brains, human infants require energy for growth and to combat illnesses. During the first 4 to 9 months, as they increase their fat reserves, infants also face heightened exposure to pathogens and nutritional challenges. Breastfeeding alone may not suffice, necessitating the introduction of nutrient-rich foods to meet growing demands. Historically, such nutritional supplements were not readily available, making baby fat a critical energy buffer during these transitional phases.

So while my round belly didn’t offer warmth, my mom was onto something—baby fat has its advantages after all.

Morgan K. Hoke is an anthropologist specializing in growth, nutrition, and health from a biocultural perspective. She obtained her Ph.D. in anthropology and M.A. in public health from Northwestern University in 2017. Follow her on Twitter @MorganHoke.