Ants: Nature’s Unseen Farmers Outperforming Humans

Written on

Chapter 1: The Ancient Cultivators

For tens of millions of years, ants have been diligently harvesting crops, often achieving results superior to those of humans.

Humans take pride in cultivating various plant species, such as wheat and potatoes, which have enabled the rise of cities and civilizations. Yet, there exist unassuming creatures that have engaged in similar agricultural practices. Fungus-farming ants have domesticated fungi from the Leucocoprineae family, nurturing these organisms deep within their nests, akin to how we cultivate plants in fields. Their agricultural techniques are so sophisticated that they elicit envy from human farmers.

Ants from the Acromyrmex and Atta genera are particularly skilled, creating "mushroom farms"—chambers that can reach the size of a soccer ball. One nest can house up to a thousand of these chambers, forming an underground metropolis that extends seven meters below the surface and accommodates millions of ants. In terms of soil aeration and excavation, ants outperform earthworms.

The fungal harvest is a collaborative effort. Larger worker ants cut leaves into manageable pieces and transport them back to the nest. This delivery resembles a procession of ants bearing green parasols, which has earned them the nickname "umbrella ants." If we scale their world to human proportions, a worker ant would cover a distance of 15 kilometers at a speed of 26 kilometers per hour, surpassing the world marathon record set by Kenyans.

Section 1.1: Nurturing the Crop

Inside their nests, smaller worker ants process the plant material into a mushy substance, forming beds that are segmented by sponge-like corridors. They cultivate fungi by transferring tiny strands to new plots while frequently replacing leaf litter with fresh material, discarding the old into mounds away from the nest. Constant vigilance is essential, as ants patrol their plots, using their antennae to detect and remove any intruders.

The dense cultivation makes them susceptible to pathogens, but umbrella ants have developed effective defense mechanisms. If a worker ant identifies a threat, the entire colony mobilizes to eliminate it. This high-stakes weeding task is often assigned to the oldest ants, who are nearing the end of their life cycle.

However, they face greater threats from the Escovopsis genus, a fungus that specializes in attacking their crops. If these invaders appear, the ants resort to chemical defenses, revealing their remarkable foresight.

Section 1.2: Chemical Warfare Against Fungal Invaders

Professor Cameron Currie from the University of Wisconsin-Madison discovered that the white, waxy substance covering some worker ants is actually a special bacteria. These bacteria produce compounds that are effective against the ants' primary crop pathogen.

Years later, Dr. Matt Hutchings from the University of East Anglia uncovered that these ants can deploy multiple substances that inhibit bacterial and fungal growth. This strategy is akin to multi-antibiotic treatments used in human medicine. Additionally, Dr. Hutchings identified a new compound similar to nystatin, which could potentially treat fungal infections in the future.

Recently, Professor Jacobus Boomsma’s team observed umbrella ants in Panama utilizing another method to combat harmful fungi. All ants possess metapleural glands, which can secrete formic acid, a powerful substance used to treat infected areas of their crops. This acid is produced by specific worker ants tasked with weed control and is only deployed when necessary.

Chapter 2: The Harvesting Process

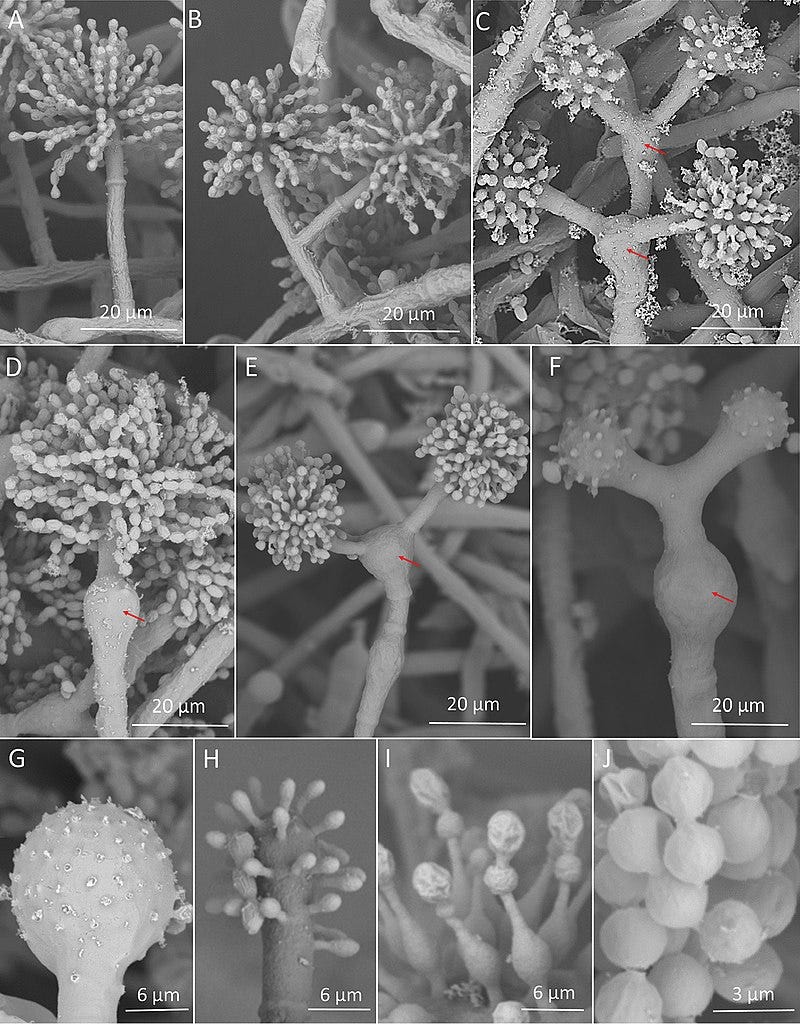

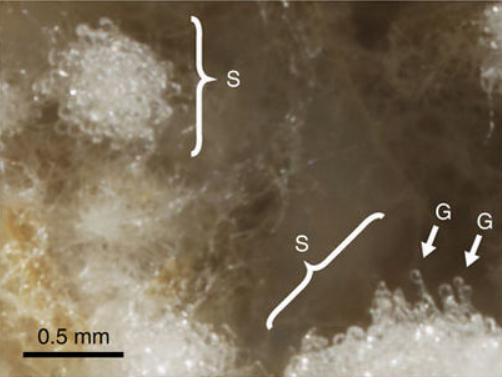

Ants have been employing advanced agricultural techniques for millions of years, leading to the production of gongylidia—swellings at the tips of their cultivated fungi’s hyphae. These microscopic structures, rich in glycogen, amino acids, and fats, serve as food for larvae, worker ants, and the queen.

Gongylidia, measuring just 30–50 micrometers in diameter, offer a digestible source of energy. Ants do not digest most of the enzymes present in gongylidia but excrete them in new crop areas, enhancing soil fertility through this natural composting process.

Section 2.1: The Role of Ants in Seed Dispersal

Plants heavily rely on ants for seed dispersal, with at least 11,000 species depending on these insects. Research shows that myrmecochory—seed dispersal by ants—has evolved independently in various regions over 147 times. In just one hectare of forest, numerous ant nests can facilitate the growth of new plants.

Over a century ago, Swedish naturalist Rutger Sernander estimated that in favorable weather, a single ant colony can move over 29,000 seeds in just 80 days. Ants are not altruistic in this behavior; seeds have adaptations called elaiosomes, which are nutrient-rich appendages. When ants discover a seed with an elaiosome, they transport it to their nest, feeding the larvae and discarding the rest in the trash pile—creating a fertile environment for new plant growth. Thus, ants are often credited with the invention of composting.

Attention all readers!

As content creators on Medium.com, we face minimal compensation for our hard work. If you find value in my articles, please consider supporting me on my “Buy Me a Coffee” page. Your small contributions can make a big difference in fueling my passion for creating quality content. Thank you for your support!